In Christianity there’s a lot of talk about God’s love—the claim that God loves us, and that we must love God in return. But what if God isn’t a person, not really. What if we just think of “him” that way? What if we’re just projecting our patriarchal consciousness onto an ineffable mystery? What if our idea of God is just that—an idea. Can you love an idea? Can an idea love you?

Honestly, I don’t get it.

But just because I don’t get it doesn’t mean it’s not worth investigating. If I distrust traditional God-concepts, I distrust my own concepts even more.

Joseph Campbell to the Rescue

Everyone’s favorite scholar of world mythology and comparative religion Joseph Campbell had a useful way of thinking about this problem. All God-ideas, he said, are like masks—masks of eternity. Like Carl Jung before him, Campbell chronicled the ubiquitous presence of archetypes around the world—universal ideas that well up from the collective unconscious and take specific, local form as mythic images. Among them, the most significant is the Supreme Being archetype. Across all cultures and traditions you find this idea—that there is a deeper reality hidden beneath the surface, and that this deeper reality is in fact the source of, and superior to the surface reality. The Supreme Being is itself ineffable, that is, cannot be conceptually known or expressed in words. So artists, shamans, and storytellers make a beautiful mask. We need something to look at and talk about right?

From where do the mask-makers draw their inspiration? From their immediate environment and from the prevailing cultural and sociological norms. For the Navajo, the gods are coyote and raven. For Pacific Islanders they’re dolphins and sea turtles. In patriarchal cultures God is a man, while matriarchal cultures cleave to the Great Goddess. In simply Freudian terms, we project onto the heavens our own notions of power and place. And beyond environment and sociology, there is a third factor that molds our masks of eternity—our deep and abiding needs.

In an agricultural society, God brings rain and the ripening of the grain—a God of abundance in a world of scarcity. If basic survival has been attained, the needs grow more nuanced—now a God of love, mercy, forgiveness, healing, and reunion appears.

In the Hebrew Bible, where Christianity and Islam draw their inspiration, we find a small tribe in the deserts of the Levant struggling against its many neighbors in a state of near-continual warfare. So the God of early Abrahamic monotheism wears many hats, (hats distributed more widely in the polytheistic systems that surround them), the creator, the judge, the punisher, and the warrior who authorizes morally dubious violence against any and all threats. In monotheism your God is a multitasker.

Other wisdom traditions like Daoism stop short of personifying ultimate reality, calling it instead Dao, literally “the way.” Dao, like the Force in Star Wars, is a non-local, impersonal energy present within all things. Because Dao is not a conscious entity is doesn’t require worship. Instead, Dao is the flow in which we find ourselves, to be allowed and aligned with.

In India they split the difference. What we in the West call Hinduism is really scores of schools (darshanas) that vary widely on the question of God. The Vedanta darshana holds that ultimate reality is Brahman, the sacred ground of being beyond all thoughts and forms, while other Hindu sects populate the cosmos with hundreds of gods and goddesses like Vishnu, Shiva, and Mahadevi (the Great Goddess).

So what are we to do with this bewildering variety of God-concepts?

In Campbell’s analysis, the masks of eternity are both good news and bad news. The good news is they tell us where to direct our attention, and if the masks are good, they might even convey some of the ineffable qualities of the mystery behind them. But the bad news is they tell us more about the people who made them than they do about the mystery they claim to convey. For Campbell, masks hide more than they reveal. The real tragedy in the world is the incalculable human suffering born from the womb of our forgetfulness—we forgot that we made the masks, and fall into the ignorant insistence that our mask is God. This is when the masks—our God-concepts—become more than problematic. They become idols, the very thing the Hebrew God forbids in the second commandment. They give rise to internecine violence, and they hamper our deepening connection with the sacred source. We think we are worshipping God, but we are really just worshipping our own idea of God. In the end, our mask of God becomes the final obstacle to overcome. If you really want to know God, you have to forget everything you know about God.

“One of the main functions of organized religion is to protect people against a direct experience of God.” ~ Carl Jung

This is why fourteenth century Christian mystic Meister Eckhart wrote that, “God is not found in the soul by adding anything, but by a process of subtraction.” And in Mahayana Buddhism ultimate reality is framed as Shunyata, or Emptiness.

Are we here to experience God outside of words and concepts? Or are we here to worship our own idea of God? How liberating would it be for all of the world’s religions to gather and meet and commit to seeing the one reality behind all of the masks?

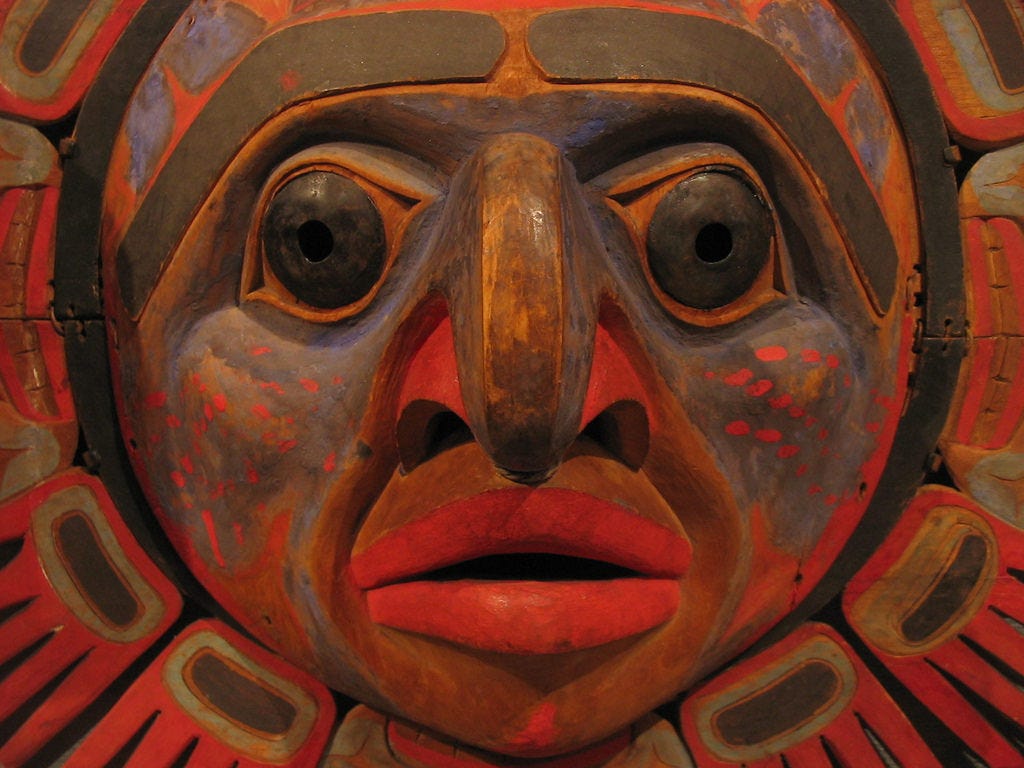

Nuxalk Sun Mask, American Museum of Natural History

God Without a Face

What if religions are like languages—they’re all true, they’re all valid, and they all work. Religions, like languages, are systems of signs and symbols that point to something beyond, while giving us the means to share with one another our burgeoning wisdom. As Alan Watts said, the menu is not the food. The map is not the place. When we insist that our mask is real and all the other masks are false, we have confused the referent with that to which it refers. It is a simple mistake. Far from being an atheist attack on religion, this perspective honors the universal, archetypal experience of ultimacy, while celebrating the diversity of our creative mask-making efforts. We are not wrong to want to know God, to want to connect with the sacred, formless source from which all forms arise and to which they return. This is after all the very meaning of religion, from religio: to link back, to reconnect. But to cling to one mask while condemning others is debilitating spiritual impoverishment.

Many Paths to the Summit

Which brings us back to our original question—what of God’s love? Let’s see how Hinduism handles it.

In the Hindu system there are four traditional paths (margas) or methods (yogas)—one for each of the four personality types. For the intellectually oriented, Jnana yoga is the path of knowledge. Here one moves toward Brahman-realization through study and rational discourse. For the action-oriented, Karma yoga is the path of selfless service. Here one turns everyday work into sacred action, working not for private gain but for the good of all. For heart-centered people, bhakti yoga is the path of devotion. This path is rooted in the broken-open humility born from the worship of gods and goddesses. And Raja yoga is the path of discipline for those drawn to experiencing transformation. Here one undergoes a process of mind-body-spirit purification and moral training through breath work, body work, and seated meditation.

Jnana yoga is built on a non-dualistic concept of ultimate reality—that we are to realize our oneness with Brahman. Bhakti yoga is built on a dualistic concept of ultimate reality—that through deep immersion in loving relationship with deities we surrender into that same ultimate oneness. As nineteenth century Hindu saint Ramakrishna put it, “Many paths to the summit.”

Bhakti yoga never moved me—I don’t know why, it just didn’t—but jnana yoga drew me like a magnet. I couldn’t stay away. To me, books and ideas were portals to deeper worlds far more real than the superficial sadness of school and what passed for society. I’d skip the homecoming dance for a walk through the hills with a trusted friend, wandering and wondering as if our lives depended on it, convinced that we were on the edge of something deep and meaningful.

My Come to Jesus Moment That Wasn’t

When I was 19-years-old in Ventura, California, I had a girlfriend named Nancy Ingrum. She was a Christian. I was not. But I followed her around like a puppy. And I was just religion-curious enough to follow her to church a time or two. It didn’t do much for me. I remember a Baptist preacher with perfect televangelist hair who seemed as bored with his sermon as I was. But I liked the family dinners at her house afterwards.

One time Nancy took me to an evening revival meeting in a downtown warehouse where a youth pastor in jeans and a graphic T-shirt led a fiery Billy Graham-style come-to-Jesus revival. It was the late-seventies, and the Jesus Movement was going strong. After his passionate but utterly unconvincing sermon he invited all who wanted to be saved to come up front and kneel at the altar to receive Jesus Christ as their own personal Lord and savior. As dozens of teenagers flooded to the front I sat on my hands. Nancy looked over. I didn’t move. She gave me a little nudge. Nothing. The last thing any of us needed was my empty, performative conversion. I don’t remember much after that, but the ride home was a little, um, awkward.

The next year I moved up to Santa Barbara to attend UCSB as a religious studies major. Nancy moved to Maui. A few long, sad, last phone calls and it was over. She found a new boyfriend a little too fast for my liking. But it was none of my business now.

Christianity as Bhakti Yoga

For decades, Christianity remained a closed door for me. But from somewhere over the horizon a soft breeze was moving the door on its hinges.

A few years ago I came across Philip Goldberg’s remarkable book American Veda: From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation—How Indian Spirituality Changed the West. I built a talk around it called “Vedanta Comes to America.” A mutual friend who attends services at the San Diego Vedanta Monastery brought the sole resident contemplative, Swami Harinamananda, to the talk. We met afterwards and soon became friends. He began inviting me to lecture at the monastery a few times a year at their regular Saturday morning lecture series. It was there that I experienced first-hand the remarkable confluence of jnana and bhakti yoga that is the trademark of the Vedanta Society.

At the San Diego Vedanta Monastery Swami Harinamananda leads his parishioners in puja (worship) in the shrine room for an hour before each lecture. At first I didn’t get it. In my own study I always understood Vedanta as a strictly jnana yoga experience. But here was a community or parishoners singing and chanting Sanskrit prayers and songs of devotion to the Great Mother and other deities alongside their deep commitment to philosophical investigation. Despite the beauty of these rituals, it set up a cognitive dissonance in me. So it was possible to live rooted in the head and heart at the same time, to move from either/or to both/and. I had worked so hard for so long to keep them separate. It was a relief to feel my rigidity softening.

And then there’s this—my longtime love of European cathedrals—St. Paul’s in London, Grote Kerk in my parent’s hometown, Haarlem, the Netherlands, Notre Dame de Paris, Hallgrimskirkja in Reykjavik, Iceland, and Easter service in the Washington National Cathedral in 2013—a high church Episcopalian Cathedral before I even knew what Episcopalianism was. I don’t know why I was drawn to these places. I didn’t care why. I just wanted to be there. My footsteps led me through the door to stand rapt in awe—those vaulted spaces, as vast as imagination, as empty as the boundless awareness of my deepest meditations—empty enough to hold the mystery intact.

I could prattle on about architecture, music, incense, stained glass, and centuries of history and tradition, but that’s just my old jnana yogi self trying to find reasons, trying to explain. Part of me—a growing part of me—was losing interest in reasons and explanations.

And all along the labyrinthine path was my Trappist guru Thomas Merton. From The Seven Storey Mountain to New Seeds of Contemplation to The Way of Chuang Tzu and countless other writings on Zen Buddhism, Christian mysticism, and the solitude of the contemplative life, Merton became the voice in my head, a trusted friend, a brother, a fellow traveler, a muse. And he showed me how Christianity done right could be a powerful jnana/bhakti synthesis of immense depth and power.

The Mountains are Calling

From all of these voices, including my own, I was learning that you could experience God without knowing what God is.

I found God, or Depth, in the mountains, forests, deserts, and beaches of my beloved California, and throughout the rest of the American West. I found God or depth in the books of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Herman Hesse, Edward Abbey, John McPhee, Farley Mowat, Tom Robbins, Kurt Vonnegut, Peter Mathiesen, and J. R. R. Tolkien. In the poetry of Walt Whitman, Mary Oliver, Rumi, and Charles Bukowski. In the study of film, all the classics—foreign and domestic. I dove into great music the way I dove into Sierra swimming holes—totally and without reservation, and I found God, or Depth there too. I didn’t want to stay dry, or safe, or isolated. I wanted to feel every cell opening, every thought re-forming, every fear receding, shown for the lie it was. To me, God was best found in the liminal spaces, the in-between, in the cracks that formed when things fell apart, in the places others overlooked.

And I found depth and significance in my own struggles to create—as a writer, photographer, poet, songwriter, and performing musician. Not in the outcomes, but in the process—in the simple making and doing. To immerse yourself in art-making is to dance with the sacred.

And this too: I found God, or Depth, in the sea. All the years of my youth I surfed the waves between Ventura and Santa Barbara, with friends, or alone. Held aloft on a cerulean plane, the liminal space between earth and sky, a liquid field where beneath the surface unseen currents move and whales sing clan songs of timeless beauty. It was home to me, safer than the madness of high school, saner than the chaos of my own mind. Here it felt good to belong somewhere, like I was safe in the cosmos, like what I did—my freedom, my choices, my actions, the meandering wake my board left on wave faces—mattered as much as anything else, or more. Surfing gave me my own significance, my own power, my own peace. I dream of those surf sessions all these years later—the eternal now of a treasured ritual theater of salt and sun and surrender and assertion.

From No Church to High Church

So, given my long path as a religious skeptic, as an agnostic bordering on atheism, with deep resistance to devotion of any kind, how is it that I’m now able to participate in high church worship at an Episcopalian Cathedral? Here’s how. I don’t think about the face of Jesus, or of the Father, or of the Holy Spirit. I don’t think about much at all. I feel. I let these ancient images and liturgies loom over me as masks of eternity.

The morning light through the stained-glass windows make purple, green, blue, and red beams in the frankincense smoke. The plainsong chant of the 42nd Psalm sung by the choir shifts me. “As a deer longs for flowing streams, so I long for you God.” Something opens, something rare, something nameless, something sublime, something rich and profound. I usually cry. Good tears. Tears that feel like they’ve been waiting years to break free. And in the cleansing of this catharsis I at once soar and am rooted into something real, more real than anything else.

For some in the congregation, it is Jesus Christ who elicits this reverence—their Christianity is unabashedly bhakti and rooted in the dualism of deity and devotee. For me, it is the nameless presence behind the mask, what Christ calls “the Father in me,” that pulls me in. Is God up there, or in here? The answer is yes. All religions meet in the experience of Being or Depth or Oneness in the here and now. In the Episcopalian liturgy we meet God in the cup, in the wine, in the bread, and in the love that weaves us all together. Of God, Paul says “in him we live, and move, and have our being.” (Acts 17:28) And that is precisely what the Vedanta tradition says of Brahman—that ultimate reality is what we are, only we don’t know it. Plato was right—all learning is remembering. All out-going is homecoming.

Love is the only word left when all the other words fail. This is the food the soul longs for. This is the depth behind all the masks. This is the love of God. We needn’t conceptualize God as a person to love God or experience God’s love for us. We have only to real-ize it. Love is the name of the nameless oneness that we Are.

This is God without a face.

“I need to be silent for a while. Worlds are forming in my heart.” ~ Meister Eckhart

Thanks for articulating pieces of my own spiritual journey that at times has felt contradictory and nonsensical. The Divine dwells within all of it. Face or no face. I think the Beatles had it right. It’s love, love, love. The greatest of all. And all you need. ❤️🙏🏼

Brilliant!